Paris Psalter

David Composing the Psalms

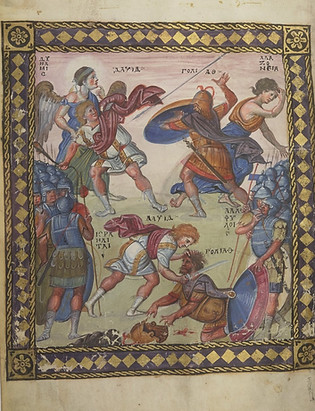

David killing the lion

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Byzantine (Constantinople), second half of 10th century

Tempera and gold leaf on vellum; 449 folios; 37 x 26.5 cm

The Paris Psalter is the best known example of Byzantine Psalter illustration, long supposed to be typical of the genre but now recognized as being exceptional in size and in the beauty of its script and wealth of full-page illumination. Beyond the text and catenae, it now contains eight miniatures devoted to the life and person of David and six (originally nine?) illustrations of the Odes. The David pictures emphasize the virtues of the ideal emperor, often through the presence of personifications, both classical and Christian. It has proposed that the book was made for the future emperor Romanos II at the behest of his father, Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos.

Read more at The Paris Psalter (Khan Academy)