The so-called Palace of the Porphyrogenitus (Turkish Tekfur Sarayı) was located in the region of Blachernai (modern Ayvansaray) in the northwestern corner of Byzantine Constantinople. Its name likely refers to the porphyrogenitus (“purple-born”) Constantine, son of Emperor Michael VIII (1259–1282). It was built on a hill above the Blachernai Palace, as a separate yet closely related complex. It opened as a museum in 2019 following a controversial reconstruction.

The structure seems to have been constructed around 1261-1291 following the Byzantine reconquest of Constantinople. It has also been argued that it has an earlier phase perhaps dating to the reign of Manuel I Komnenos (1143-1180) when he constructed new city walls by the Blachernai Palace. Even if it has an earlier phase, the current structure seems related to Michael VIII’s restoration of the Blachernai Palace following his recapture of Constantinople in 1261. It was probably the “House of the Porphyrogennetos” (οἶκος τοῦ πορφυρογεννήτου) mentioned in the 14th century, which was associated with the third son of Michael VIII (1259–1282), the porphyrogennetos Constantine, who was held there under house arrest after 1293 by his brother Andronikos II Palaiologos (1282-1328). The imperial epithet, porphyrogenitus (πορφυρογέννητος “purple-born”) designated children born after their father had become emperor. Michael VIII perhaps chose Blachernai to be his official residence as it was also the main residence of the Komnenian emperors, whose reputation and fame still loomed large at the time. As a distant relative, Michael VIII was keen on associating himself with the Komnenian dynasty, even adding Komnenos to his patronymic. While it is unclear how the Palace of the Porphyrogenitus and the main Blachernai Palace complex were connected, their proximity is surely significant. The Palace of the Porphyrogenitus, which is located on a hill to the south, is around 500 meters from the palace’s northern terrace wall.

The palace played an important role in several key moments of the 14th century. The “House of Porphyrogenitus” is mentioned when Andronikos III (1328-1341) took control of the government from his grandfather Andronikos II in 1328. Andronikos III briefly resided here to be close to his grandfather, who officially retained his imperial insignia and continued to reside in the Blachernai Palace. It also played a key role at the end of the Civil War of 1341-1347, which started when John VI Kantakouzenos (1347-1354), chief adviser and general for Andronikos III (1328-1341), failed to secure the regency for John V after the emperor’s death. Anna of Savoy, wife of the late emperor, instead became the regent for her son John V, and joined Patriarch John XIV of Constantinople and Alexios Apokaukos in opposing John VI Kantakouzenos. In 1346, Kantakouzenos was crowned emperor in Adrianople and the following year he entered Constantinople by breaching the Golden Gate, which had been walled up. He then marched to the House of the Porphyrogenitus above the Blachernai Palace, where the Empress Anna of Savoy was residing. Kantakouzenos forbad the palace to be attacked, and began negotiations for her to surrender. However when she sent messengers away, some officers of Kantakouzenos became so infuriated that they disobeyed his orders, set fire to one of the gates, and stormed the palace. In the end, Anna was persuaded by her son John V to discuss terms of peace, and once the agreement was signed, the gates of the palace were opened to admit Kantakouzenos as the senior emperor.

John V (1341-1391), who married Helena, the daughter of John Kantakouzenos, was forced remain in the background until a new civil war broke out in 1352. In 1354, John was able to slip into Constantinople at night, after which word spread and the following day mobs began to attack the houses of known supporters of Kantakouzenos. John encamped outside the House of the Porphyrogenitus, just as Kantakouzenos had done a few years before. The mob helped storm the palace, but the emperor's Catalan guards drove them back. John sent a negotiator to the palace, and Kantakouzenos agreed to joint rule, as they had agreed in 1347, though this time Kantakouzenos abdicated a short time later.

The map of Constantinople made by Buondelmonti around 1420 labeled Tekfur Palace as Palatium Imperatoris, suggesting that it might have served as the main imperial residence in the final years of the Palaiologan era. Following the Ottoman conquest, Jewish families from the region of Thessaloniki were settled in the area of the palace. In the 16th century, the palace and a nearby cistern were used to house the sultan’s menagerie. During this time, it began to be called Tekfur Sarayı (“Palace of the Sovereign”) in Turkish, though it was commonly called the Palatium Constantini (“Constantine’s Palace”) by foreign visitors during this period. In the 19th century, it was incorrectly identified as the Hebdomon Palace, and it was commonly called the Palace of Belisarius. One legend claims that the famous “Spoonmaker's Diamond” (Kaşıkçı Elması) was discovered here, though the legend that it was discovered at Yenikapı is more commonly cited; the diamond became part of the treasury of Topkapı Palace during the reign of Mehmed IV (1648-1687).

In the early 18th century, it was decided to bring craftsmen from Iznik, and subsequently a workshop was set up in the courtyard of Tekfur Palace in 1719. The most famous example of the tiles made here can be found in the Fountain of Sultan Ahmed III (1728). Another noteworthy example is a depiction of the Kaaba in Mecca in Hekimoğlu Ali Pasha Mosque (1734). Glass began to be produced at the site in the early 19th century glass. Around the same period, Tekfur Palace was used as a Jewish poorhouse (Yahudihane) until a fire devastated it in 1864. This completely destroyed the interior, leaving it a shell, while other features, such as its main balcony, were severely damaged. Kastoria Synagogue, which served the Jewish community here, was located a short distance east of the palace; the final version, now lost, was in the 19th century and continued to be used until 1937.

There is evidence of repairs to the Tekfur Palace complex made during the Ottoman era, though much more substantial changes were made in more recent years. Restoration work was made between 1955 and 1970, during which time, new marble columns were added and the debris in the palace remains and courtyard was removed. More recently, the building was opened as a museum in 2019, following its controversial reconstruction involving rebuilding the former empty shell of the three story structure and the additions of interior and exterior elevators.

Architecture

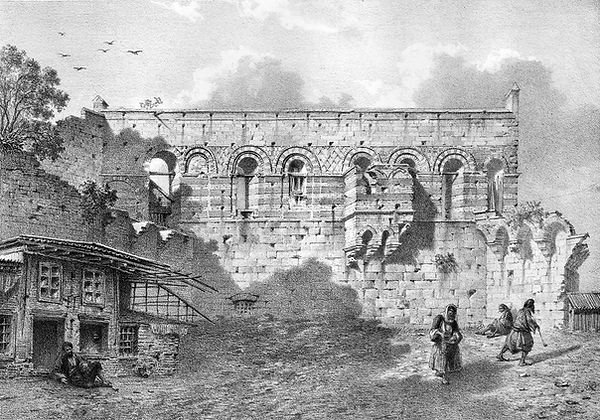

The Palace of the Porphyrogenitus was a three-story rectangular structure with an open northern façade facing a courtyard constructed between the main and outer Theodosian walls. It has a rather prominent location as it is located on a hill at a major bend at northern end of the Theodosian Land Walls, just south of the Walls of Manuel I Komnenos.

The three-story structure of the palace complex is over 25 meters tall, with its interior dimensions measuring around 10x15 meters. The exterior has two zones: the lower level has massive ashlar masonry, while the upper floor has colorful brickwork that is elaborately decorated. The lowest level has four large arches open to the central court and domed vaults supported by six marble columns. The middle floor, which had a flat wooden ceiling and niches or cupboards flanking the windows, may have been subdivided into apartments. The upper floor, which was probably a single large room that functioned as a vast throne room, had windows on each side and was covered with a low-pitched roof. Being located on the upper floor would have required those who entered the palace ascended to the level of the upper floor in order to take part in the audience before the emperor. This floor also had a balcony on the southeastern corner facing into the city and a tiny chapel projecting out on the south façade, both of which were supported by corbels. The balcony’s corbels had lion, ram, and eagle protomes, which are now lost, and was likely involved in imperial ceremonies. The upper zone and inner façades consist of regular alternating bricks and limestone ashlar with very thin mortar joints. The arches of the windows have banded voussoirs, outlined with green-glazed ceramic rosettes, and tilework in a variety of geometric patterns filling the window spandrels. The ground-floor arcades probably had keystones with Palaiologan emblems.

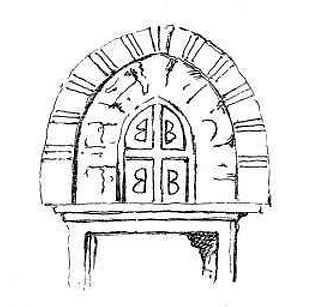

This three-storied structure was connected by an archway to Tower 97 of the Theodosian Walls, which may have served as a sort of donjon (inner tower). The pointed arch was documented in the 19th century before it was lost, and traces of the arch can still be found on the exterior wall of the palace. The masonry of Tower 96, which differs significantly from other towers of the Theodosian Walls, shows several phases belonging to the Byzantine and Ottoman eras. A significant section of this tower was rebuilt in the mid 20th century. It has arrowslits as well as corbels for a balcony facing the city. There is a tower on the courtyard’s outer wall around 15 meters north of the main palace structure. It has several phases of construction and was heightened at a later stage. There is an exterior gate just north of this tower, which has a marble lintel resting on marble consoles. This gate, which was around 3.5 meters, was largely buried at some point and now is below the current level of the ground. Remains of another Late Byzantine façade are located above the outer wall to the north, though not enough has survived to allow a reconstruction. A beta-cross emblem of the Palaiologan dynasty, now at the Patriarchate, was over one of the windows of this façade. There is a corridor within the exterior curtain wall, leading under the second façade and terminating the remains of a tower that was built into the Komenian Wall. There are remains of an older wall just to the east; it perhaps belongs to the Heraclean or Theodosian phase of the land walls and points towards the Mumhane Wall, which itself is an earlier phase of the Blachernai Walls. There is no evidence of a larger tower from the inner wall to the east, though there are remains of corbels from another balcony on the outer curtain wall facing the city.

The location of the palace between the city walls suggests the need for both external and internal security, which is consistent with what is known about urban mobs in Constantinople. Fortified residences for protection against both internal and external attacks were likely common in Constantinople during the Late Byzantine era, as can be seen in the civil wars of the 14th century. There are possible remains of two other fortified Late Byzantine palaces at Mermerkule and the Tower of Eirene in the city, which are possibly associated with Theodoros Palaiologos Kantakouzenos and Lukas Notaras, respectively. John V also resided at a fortified palace, the Kastellion of Chryseia, by the Golden Gate around 1390. However, the design of Tekfur Palace is markedly different from these other structure in particular ways. As its defensive qualities seem to be overstated, it might be following the model of the tower house, which had become a common aristocratic residence following the collapse of the Byzantine frontier in Anatolia. The defensive features, then, would have likely emphasized the prestige of landownership and power of its residents. While Tekfur Palace is quite unique for Constantinopolitan architecture, it can compared to the Laskarid Palace at Nymphaion near Magnesia (modern near Manisa) or even the tower house of Niketiaton Castle (modern Eskihisar) in Bithynia. Its layout has also been compared to Italian palaces from around this period, with their three levels serving utilitarian, public, and private functions. However, as in the Palace of the Despots at Mystras, the upper story probably functioned as its throne room, while its middle floor had private apartments. There was also a Genoese Palazzo Comunale in Galata, which was rebuilt in 1315, that could have introduced models of Italian palaces. Its glazed ceramic rosettes and tilework, while uncommon among the surviving monuments of the city, has pronounced affinities with the architecture of Mesembria (modern Nesebar, Bulgaria). Another interesting feature is how its openings lack vertical alignment, suggesting it belongs to an anti-classical trend, despite classicizing architectural tradition generally dominating Constantinople at the time.

The arches of the windows have banded voussoirs, outlined with green-glazed ceramic rosettes, and tilework in a variety of geometric patterns filling the window spandrels.

Elaborately decorated brickwork with glazed ceramic rosettes and tilework of Archangels and St. Paraskeva churches of Mesembria/modern Nessebar, Bulgaria

Chapel

Remains of Balcony

Tower 97

Aerial photo by Kadir Kir

Aerial photo by Kadir Kir

Michael VIII Palaiologos

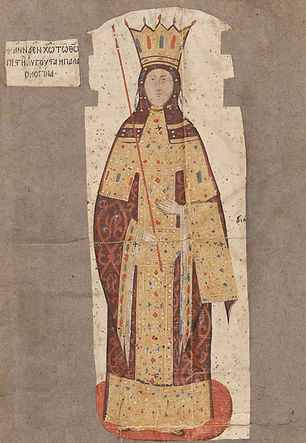

Codex Marcianus Gr. 404 (14th century)

Andronikos III Palaiologos (fol.2r) and Anna of Savoy (fol.4r)

The Palace of Porphyrogenitus is probably related to Michael VIII’s restoration of the Blachernai Palace. The palace played an important role during the reigns of Andronikos III, John VI Kantakouzenos, and John V as well as Anna of Savoy’s regency.

John VI Kantakouzenos (Gr. 1242 fol.5)

From Cristoforo Buondelmonte (ca. 1422)

Mosaic of John V Palaiologos at Hagia Sophia

Vavassore (ca. 1530s)

From map by Piri Reis (16th century)

From panorama of Constantinople by Melchior Lorck (1559)

.jpg)

Detail from Sebastian Munster (1550)

Based on Vavassore (c. 1520)

From Itinerary by Fynes Moryson (1617)

Here [at Constantinople] be the ruines of a pallace upon the very wals of the City, called the pallace of Constantine, wherein I did see an Elephant, called Philo by the Turkes, and another beast newly brought out of Affricke (the Mother of Monsters), which beast is altogether unknowne in our parts, and is called Surnapa by the people of Asia, Astanapa by others, and Giraffa by the Italians, the picture whereof I remember to have seene in the Mappes of Mercator; and because the beast is very rare, I will describe his forme as well as I can. His haire is red coloured, with many blacke and white spots; I could scarce reach with the points of my fingers to the hinder part of his backe, which grew higher and higher towards his foreshoulder, and his necke was thinne and some three els long. So as hee easily turned his head in a moment to any part or corner of the roome wherein he stood, putting it over the beams thereof, being built like a Barne, and high for the Turkish building, not unlike the building of Italy, by reason whereof he many times put his nose in my necke, when I thought myselfe furthest distant from him, which familiarity of his I liked not; and howsoever the Keepers assured me he would not hurt me yet I avoided these his familiar kisses as much as I could. His body was slender, not greater, but much higher then the body of a stagge or Hart, and his head and face was like to that of a stagge, but the head was lesse and the face more beautifull: he had two homes, but short and scarce halfe a foote long; and in the forehead he had two bunches of flesh, his ears and feete like an Ox, and his legges like a stagge. The Janizare my guide did in my name and for me give twenty Aspers to the Keeper of this Beast.

Drawing by W.H. Bartlett (1838)

Drawing by Eugène Flandin (1853)

Drawing by Salzenberg (1854)

Drawing by Salzenberg (1854)

.jpg)

Drawing by Mary Walker (1869)

Dimitriadis Efendi (1884)

Photo by Pascal Sébah (c. 1870)

.jpg)

Photos by Guillaume Berggren

Photo by Guillaume Berggren (c. 1875)

Photo by Basile Kargopoulo

Photo by Sébah & Joaillier (after 1883)

Photos by Sebah & Joaillier (1880s-1890s)

From Meyer-Plath & Schneider (1943)

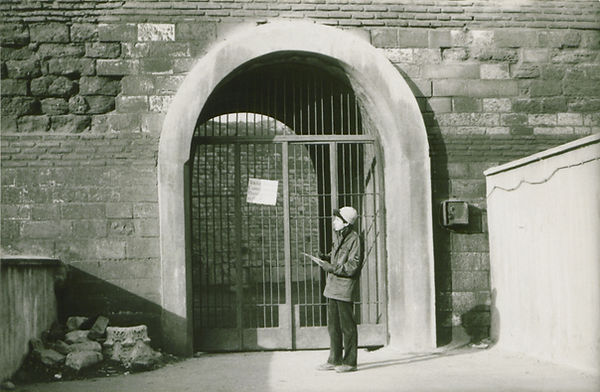

Photo by M. Erem Çalıkoğlu (1982-1998)

Four betas: βασιλεὺς βασιλέων, βασιλεύων βασιλευόντων

“King of Kings, Ruling over Rulers”

This Beta-cross emblem of the Palaiologan dynasty was originally located over one of the windows of the northern façade. This slab, now at the Patriarchate, was located at the Church of Panagia Sudas (“By the Moat”) near Eğrikapı until recently. When it was moved to the Patriarchate, a plaster copy was made to replace it. A similar slab was over one of the Genoese Walls of Galata.

At the Church of Panagia Sudas near Eğrikapı (1936)

From the Nicholas V. Artamonoff Collection

Drawing by Mary Walker (1869)

Drawing by Salzenberg (1854)

Meyer-Plath & Schneider

Funerary inscription in Tower 97 (Tekfur Palace Tower 1)

+ Ἐνθάδε κατάκιτ͜ει Σα…

“Here lies Sa…”

According to one legend the famous “Spoonmaker's Diamond” (Kaşıkçı Elması) was discovered here, though the legend that it was discovered at Yenikapı is more commonly cited.

Gate of 19th century Kastoria Synagogue

Tekfur Palace Tiles

Fountain of Sultan Ahmed III (1728) is decorated with Tekfur Tiles

Tekfur Tiles depicting the Kaaba in Mecca

At Hekimoğlu Ali Pasha Mosque (1734)

Pervititch. Plan d'assurances. Egri-Kapu. Tekfur-Seray. (Corne d'Or) No: 30 (1928)

Axonometric reconstruction by Ćurčić

Plan by Müller-Wiener

References

Müller-Wiener, W. Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul bis zum Beginn d. 17. Jh.

Meyer-Plath, B. & Schneider, A. Die Landmauer von Konstantinopel II

Salzenberg, W. Alt-Christliche Baudenkmale von Constantinopel

Van Millingen, A. Byzantine Constantinople, the Walls of the City and Adjoining Historical Sites

Mango, C. Byzantine Architecture

Ćurčić, S. Architecture in the Balkans: From Diocletian to Süleyman the Magnificent

Ousterhout, R. Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands

Güleryüz, N. İstanbul Sinagogları

Nicol, D. The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261-1453

Niewöhner, P. “The late Late Antique origins of Byzantine palace architecture” (The Emperor's House)

Macrides, R. “The “Other” Palace in Constantinople: the Blachernai” (The Emperor's House)

Feld, O. “Zu den Kapitellen des Tekfur Saray in Istanbul” (Istanbuler Mitteilungen 19)

Mango, C. “Constantinopolitana” (Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archaeologischen Instituts 80)

Eyice, S. “Tekfur Sarayı” (İstanbul Ansiklopedisi)

Ousterhout, R. “Emblems of Power in Palaiologan Constantinople” (The Byzantine Court: Source of Power and Culture)

Kazhdan, A. (ed.) Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium

Resources

Palace of Porphyrogenitus Album (Byzantine Legacy Flickr)

Byzantine Palace of Constantinople Album (Byzantine Legacy Flickr)

Tekfur Palace (Byzantium 1200)

_.jpg)

.jpg)