Chele

Şile, İstanbul

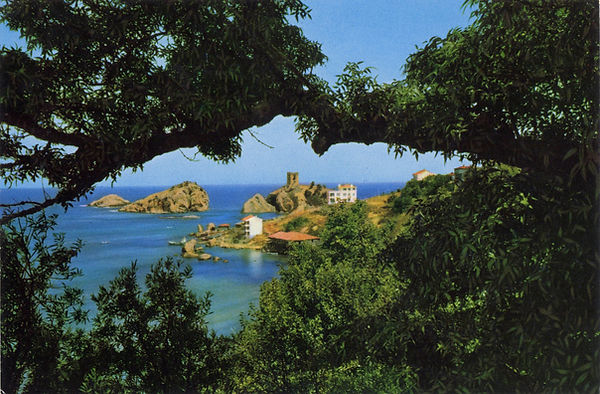

Chele (modern Şile) was a town on the Black Sea coast of Bithynia. A fortified tower is located on one of the islands protecting its harbor.

Şile Castle before its restoration

Photo by H. Sercan Sağlam

Chele (Χηλή, medieval Sili, modern Şile) was a town on the Bithynian mainland with a harbor off the Black Sea coast around 55 km northeast of Constantinople. The historic is located on a promontory with rocky cliffs. Its harbor was protected by a group of small islands, including Ocaklı Island, where Şile Castle, is located. To the west are a long sandy beach and the Türknil River (historic Artanes River). While it is popularly known as a “Genoese” castle and is often dated to the Ottoman era, historical sources indicate a tower was built on the island in the Middle Byzantine era.

History

By the Hellenistic era, Artanes (Ἀρτάνης) was a settlement with a sanctuary to Aphrodite located by the Artanes River. The location of the Artanes River (modern Türknil Nehri) suggests that the settlement Artanes could have been located around two kilometers west of the modern town center of Şile. Artanes is mentioned in several classical lists of ports (peripli) and appears on the Tabula Peutingeriana map (possibly dating to the 5th century CE). It was noted for its anchorage or harbor for small ships that was protected by a small island (likely Ocaklı Island).

By the Middle Byzantine era, Artanes was known as Chele. Another settlement east of Karpe (modern Kerpe) was called Chelai, which has often led to confusion in the scholarship. The etymology of the name Chele originally referred to “crab pincers,” and later to twin moles of harbors; thus it could have been a generic name of certain harbors that was later specifically applied to the harbor town at Şile. The last mention of the older name Artanes appears in the 8th century. A large number of Slavs (reportedly 208,000) settled by the Artanes River around 762 after the Bulgarian khan Telets (Greek Teletzes) seized power.

Chele is mentioned by Anna Komnene when discussing Alexios I Komnenos securing the Bithynian hinterland of Constantinople around 1095. Andronikos I Komnenos blinded Alexios, son of Manuel Komnenos, and banished him to the fortified Chele in 1183. According to historian Choniates, Andronikos had a tower specifically built as a place of exile. When Isaac II Angelos took power in 1185, Andronikos I fled to Chele; his attempts to continue to Crimea by ship were made impossible due to strong headwinds, leading to him being captured at Chele.

The historian Pachymeres mentioned Chele in several accounts of the early Palaiologan era. Michael VIII Palaiologos blinded the young emperor John IV Laskaris in 1261, first imprisoning him at Chele and later sending him to the castle of Niketiaton. Around 1275, the Patriarch of Constantinople, Joseph I, who was deposed by Michael VIII following his rejection of union with the Catholic Church, was first sent to the Monastery of Anaplous, then to the island fortress of Chele. After Joseph spent one winter at Chele, he requested Michael VIII to be moved to another place due to its harsh conditions and was then sent to the Monastery of Kosmidion. This religious conflict continued in the following years, resulting in John Tarchaneiotes, the leader of the radical Arsenites, being banished to Chele in 1289. Andronikos II (1282-1328) also planned to use Chele as a base in his campaigns against the Ottomans in Bithynia, but he had to return to Constantinople following an earthquake. Following the Byzantine loss at the Battle of Bapheus in 1304, the Ottomans began to expand into Bithynia, attacking Chele and Astrabete, even reaching Hieron (Yoros Castle) around 1304. When General Kassianos, who was sent to be governor of Mesothynia in 1306, was suspected of collaborating with the Ottomans, he rebelled against the emperor and seized Chele. However some of the local population seized him and handed him over to the emperor.

Chele is regularly featured in portolan charts as Sili or Silli. It first appears in the early 14th-century charts of the Genoese mapmaker Pietro Vesconte. The Russian pilgrim Ignatius of Smolensk, who was part of the entourage of the Metropolitan of Russia Pimen, passed by Daphnousias, Karphia, and stayed at Astrabike and Chele on the way to Constantinople in 1389. It is also possible that Chele is the castle Sequello in the account of Ruy González de Clavijo, who visited it on his way to the court of Timur in 1404.

The Ottoman historian Aşıkpaşazade records that Bayezid I (1389-1402), when marching from Nicomedia (Kocaeli) to besiege Constantinople, sent Yahşı Bey to take Chele around 1391, which peacefully surrendered to him. Around the same time, Bayezid I captured Hieron (Yoros) castle and also had Güzelce Fortress (modern Anadolu Hisarı) built on the eastern shore of the Bosphorus. According Evliya Çelebi, who visited in 1640, Şile had a janissary garrison, along with six hundred beautiful houses, each with its own garden.

Architecture

Şile Castle is located on the rocky Ocaklı Island to the north of the old town of Şile. It has a squarish tower measuring around 10 x 12 meters. It was apparently 15 meters tall, with three barrel-vaulted floors. It had average-sized rubble masonry with limited use of brick, though its fabric was radically altered during the 2015 restoration. Consoles on the tower’s northern façade indicated it had a balcony. There are several arched openings, which seem to have been wide windows for observation rather than arrow slits for defense. There is also a cellar under the ground level. The tower is near the southwestern corner of the island, surrounded by lower ramparts that form a long, narrow rectangle. There is also a cistern measuring 6 x 10 meters near the southeastern corner of the lower ramparts.

The castle was in extremely poor condition before the heavy-handed restoration was completed in 2015. The survey of Şile Castle before the restoration did not detect any distinctive construction phases. It has been various attributed to the Byzantines, Ottomans, and even Genoese, though there is no evidence of Genoese occupation of the island. It is often interpreted as a watchtower for observation and defense purposes and the size of the fortifications is often considered too small for settlement. However considered the primary sources and its historic context of Chele in the Middle and Late Byzantine eras have often been neglected in studies of the castle. Furthermore there are limited sources suggesting an Ottoman era. Since the highly intrusive restoration damaged the historic fabric of the building, any further analysis of the buildings seems virtually impossible, and thus it is unlikely a definitive identification can be made in the future.

While Şile Castle has frequently been identified as Ottoman, it could be dated to the Byzantine era. The masonry of Şile Castle is not so dissimilar from the masonry of other regional fortifications dating to the Byzantine era. It can also be placed in a wider context of Bithynian fortification construction activity during the Komnenian and Palaiologan eras. Following the Byzantine defeat at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, a network of fortifications was built in Bithynia during the Komnenian era. It seems that several nearby fortifications were built during this period, perhaps including Kefken Island, Darıca (Ritzion), Aydos (Aetios), and Yoros (Hieron). The first reference to fortifications at Chele indicates a tower was built here as a prison or place of exile in the late 12th century. During the reign of Michael VIII Palaiologos, another phase of fortification building took place in Bithynia, as seen as the castle of Harmantepe and Seyfiler. It is possible that the fortifications at Niketiaton were transformed from a Komnenian residential tower house to a castle during this period. Other sites, such as Astrabeke (modern Seyrek), seemed to have been fortifications where locals could have taken shelter during Ottoman attacks. These contexts suggest that Şile Castle could be a late 12th-century prison tower that perhaps was expanded into a larger fortified shelter responding to Ottoman expansion.

Photo by H. Sercan Sağlam

From Acra Melaena to the river Artanes, where there is a harbour for small vessels near a temple of Aphrodite, is one hundred and fifty stadia. From the river Artanes to Psilis, where small vessels may lie safely under the shelter of a projecting rock, not far from the mouths of the river, an hundred and fifty stadia.

Periplus of the Euxine Sea by Arrian of Nicomedia (2nd century CE)

Sources on Slavs settling by the Artanes River around 762

The Bulgars rose up and murdered their rulers, whom they hanged on a rope. They elevated an evil-minded man named Teletzes, who was thirty years old. Many Slavs fled and went over to the Emperor, who settled them at Artana. On June 15 the Emperor went to Thrace. He also sent a fleet by way of the Black Sea; it had about eight hundred warships, each of which carried about twelve horses. When Teletzes heard of the movement against him, he made allies of 20,000 men from neighboring tribes, and secured himself by putting them in his strongpoints.

The Chronicle of Theophanes

Several years later some Slavonian tribes left their own country and fled across the Euxine. Their number amounted to 208,000. They were settled by the river Artanas.

A Short History by Nikephoros, Patriarch of Constantinople

Andronikos I Komnenos banishing Alexios, son of Manuel Komnenos, to Chele in 1183

Andronikos hanged the Sebasteianos brothers on the gallows for supposedly plotting to depose him and raise to the throne Alexios Komnenos. Komnenos was the son begotten by Manuel through his illicit relations with his niece Theodora and then joined in marriage to Andronikos's daughter Irene, who was descended from the same bloodline. A short time afterwards Andronikos seized Komnenos and cast him into prison; later he maimed his eyes and banished him to Chele, a coastal fortress situated at the mouth of the Pontos, wherein a tower was built to receive him. Andronikos loathed his daughter Irene and banished her from his presence, commanding her neither to grieve nor to mourn for her husband ever so little; if she had a daughter's love for her father and felt any anguish for him who had begotten her, she would loathe her husband and convert her former affection to an equivalent hatred. But she, as was fitting, could not deny her love for her consort; she sang a doleful dirge and appeared in tatters with her hair shorn.

Andronikos I Komnenos being captured at Chele

After spending many days in the Great Palace, Emperor Isaakios moved to the palace in Blachernai, where messengers arrived announcing the capture of Andronikos, who had been apprehended in the following Niketas Choniates manner. While making his escape, he came to Chele, accompanied by a few of his attendants who had served him before his reign as emperor and by the two women he had brought with him. When the inhabitants there saw that he was wearing none of the imperial insignia, and that he was hastening to sail on to the Tauro-Scythians as a fugitive, fleeing without being pursued, they neither dared nor deemed it proper to take him into custody (they feared the beast no less that he was unarmed; for they cowered just at the sight of him); they prepared a ship and Andronikos boarded it with his followers. But even the sea was vexed with Andronikos because he had often defiled her depths with bodies of the innocent; the waves rose straight up and fell back into a yawning chasm and leaped up again to swallow him, and the ship was cast towards shore. Again and again this happened, and Andronikos was hindered from crossing over before his captors arrived on the scene.

O City of Byzantium: Annals of Niketas Choniatēs

Ottoman attack of 1304

The enemies not only attacked Chele and Astrabete, but even the fortress of Hieron, and they carried out the most terrifying of deeds, as if the Emperor were slumbering or no longer living. Nicomedia was weakened by famine and, due to lack of water, found itself in the greatest of troubles. The famous Nicaea was closed and, cut off from surrounding amenities, and it too was hampered by shortages.

The Revolt of the General Kassianos in Mesothynia in 1306

Having accepted the words of somebody else, he reported the worst against him [Kassianos]; that he had decided to form a marriage alliance with the Persian [=Turk] and make a common cause with him against the interests of the empire. For that reason he was ordered to present and defend himself before the emperor. However, being despaired, Kassianos postponed his trip to the emperor. And having gained the support of soldiers, he sent to the emperor requesting assurances for his safety from the part of the emperor and advanced without being harassed. When he established himself in Chele, Kassianos believed that he had received the guarantees for his safety. Some of the inhabitants of Chele, who happened to be in the city, made an agreement with the emperor to seize the fugitive by trickery and hand him over to those who were to lead him to the emperor.

The History of George Pachymeres

Photo from 1966

From the Journey of Ignatius of Smolensk to Constantinople (1389-92)

On Sunday we passed the city of Daphnousias, Karphia, and arrived at the city of Astrabike where the metropolitan stopped to get news of Murad, since Murad had attacked the Serbian Prince Lazar. There was news too: both Murad and Lazar had been killed in the encounter. Fearing a disturbance, since we were in the Turkish state, the metropolitan dismissed the monk Michael; Bishop Michael [dismissed] me, Ignatius; and Sergius Azakov [did the same] with his monk. We left Astrabike on the Sunday before St. Peter's Day; the next morning we left Chile, passed Rheba, and arrived at the mouth [of the Bosporus]. We passed the lighthouse, and with a very good wind, to our unspeakable joy we reached Constantinople.

Russian Travelers to Constantinople in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries

Plan from Fıratlı

View from Google Earth

References

Sağlam, H. Sercan. “Şile and Its Castle: Historical Topography and Medieval Architectural History” (ITU A|Z 18)

Belke, Klaus. (ed). Bithynien und Hellespont (Tabula Imperii Byzantini, Vol. 13)

Bakalakis, G. “Χηλή” (Byzantinisch-Neugriechische Jahrbücher, Vol. 19)

Bakalakis, G. “Untersuchung über Chelae” (Proocedings of the Xth International Congress of Classical Archaeology)

Eyüpgiller, K. K., Dönmez, Ş., Çobanoğlu, A. V. “Şile Kalesi Restitüsyon ve Restorasyon Projesi Raporu”

Fıratlı, N. “Şile ve Kalealtı” (Türkiye Turing ve Otomobil Kurumu Dergisi)

Kyriakidis, S. “The Revolt of the General Kassianos in Mesothynia (1306)”

Peschlow-Bindokat, A. and Peschlow, U. “Die Sammlung Turan Beler in Kumbaba bei Şile. Antike und byzantinische Denkmäler von der bithynischen Schwarzmeerküste” (Istanbuler Mitteilungen 27-28)

Korobeinikov, D. Byzantium and the Turks in the Thirteenth Century

Primary Sources

Falconer, W. (trans.) Periplus of the Euxine Sea by Arrian of Nicomedia

Turtledove, H. (trans.) The Chronicle of Theophanes: Anni mundi 6095-6305 (A.D. 602-813)

Mango, C. (trans.) Nikephoros, Patriarch of Constantinople: Short History

Dawes, E. (trans.) Anna Comnena: The Alexiad

Magoulias, H. (trans.) O City of Byzantium. Annals of Niketas Choniatēs

Failler, A. (ed.) Georges Pachymérès: Relations historiques

Majeska, G. (trans.) Russian Travelers to Constantinople in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries

Markham, C. (trans.) Narrative of the Embassy of Ruy González de Clavijo to the court of Timour, at Samarcand

Çevik, Mümin. (ed) Evliya Çelebi: Seyahatname

Saraç & Yavuz. Aşık Paşazade Osmanoğlulları'nın Tarihi

Resources

Chele/Şile Album (Byzantine Legacy Flickr)