Obelisk of Theodosius

The Obelisk of Theodosius was one of the monuments on the spina of the Hippodrome of Constantinople during the reign of Theodosius I in 390. It was originally commissioned by the Egyptian Pharaoh Tuthmosis III in the 15th century BC to commemorate his victories in Syria. It was erected in the Hippodrome in part to commemorate the defeat of the usurper Maximus and his son Victor by Theodosius in 388.

The obelisk is made of Aswan granite and is almost 20 meters tall. It is 72.5 meters from the Masonry Obelisk and the Serpent Column stands between the obelisks, which traces the line of the spina of the Hippodrome. It rests on an elaborately decorated base depicting Theodosius and his court at the Hippodrome. There are four bronze cubes supporting the corners of the obelisk. They rest on a sculpted Proconnesian marble base, which is around 7 square meters. Under this base is another wider marble base, which is also supported by four granite blocks set at the corners of the upper base. It was originally crowned with a bronze pinecone which was knocked off by a violence wind in 869.

The Obelisk of Theodosius was erected in the Hippodrome of Constantinople in 390. The obelisk brought to Constantinople was one of a pair of obelisks on the south face in front of the Seventh Pylon at the Temple in Karnak (Thebes). It is depicted in a scene from the Corridor of Annals alongside another obelisk. It is possible that some preparation to obtain the obelisk from Egypt took place at an earlier date, perhaps during the reign of Constantine or Constantius II. The scaffolding of the obelisk can still be seen in Karnak.

In a letter written around 362, Julian ordered an obelisk lying on the shore in Alexandria to be shipped to Constantinople, suggesting that Constantine or Constantius II had already removed it from its original position and had it transported to the docks in Alexandria. It is possible, then, that Constantine planned on moving this obelisk and the Lateran obelisk that Constantius later shipped to Rome, with the intention of moving one to Constantinople and the other to Rome. The failure to move either obelisk might be the reason for the erection of the Masonry Obelisk. If this is the case, Constantius would have had two obelisks to choose from when he had one shipped to Rome. It is also possible that there was only one obelisk, which Constantius shipped to Rome contrary to his father’s intentions, thus he had another obelisk brought to Alexandria with the intention of having it shipped to Constantinople. Regardless, it seems that this obelisk was left at the docks for more than thirty years before it was erected in the Hippodrome during the reign of Theodosius I. This also could be implied in the inscriptions, which suggests other emperors had been “reluctant” to erect it.

The inscriptions on the base are in Latin on the southeastern side and Greek on the northwestern side. There are some significant differences between the two inscriptions; only the Latin inscription refers to ‘tyrants’ (i.e. the usurpers Maximus and Victor). Furthermore, the Latin inscription states it took 30 days to erect, while the Greek inscription 32 days. The particular placement of the obelisk base seems to account for the language of the inscriptions: as Latin was the imperial language, it was oriented towards the emperor and his court, while the circus factions, as representatives of the local Greek-speaking population, faced the Greek inscription. Both inscriptions indicate that Proclus (a Lycian who held the office of prefect of Constantinople from 388 to 392) was responsible for organizing its erection. He fled Constantinople in 392 when his father (the praetorian prefect of the east) was charged with involvement in the intrigues of Rufinus, the master of offices. Assured of immunity, Proclus returned to the capital only to be executed at Sykai (modern Galata) in 393. As both Proclus and his father were condemned, his name was excised from the obelisk’s base. Following the death of Theodosius, Proclus's reputation was restored, and his name was reinscribed on both inscriptions.

The first attempt to erect the obelisk was not successful, which may explain why the Latin inscription describes its erection as ‘difficult’. It is probably only about two-thirds its original height (as seen in the depiction of the obelisk at Karnak). It is unclear when this breakage happened, but it seems likely that it occurred in Constantinople during an attempt to erect it. Its base, then, would have been altered to compensate for the loss of height and the smaller footprint.

Once Constantinople became the new capital, there was a need for its emperors to emulate older Roman models. By erecting this Egyptian obelisk in the Hippodrome, Theodosius was following the example of Augustus who erected an obelisk in the Circus Maximus in 10 BC. Erecting an obelisk evoked the Circus Maximus and with it the power of Rome. Other circuses had obelisks (such as the Circus of Gaius and Nero), yet only the Circus Maximus had two obelisks. This was a later development, as Constantius II erected the second obelisk in 357 AD. It is possible that Theodosius was comparing himself to his capital’s founder Constantine, who originally had planned on moving an obelisk to Constantinople. By erecting an obelisk, he was able to accomplish what his predecessors had not. Indeed, by erecting an obelisk, he surpassed even Constantine, and thus could be compared with the first and greatest emperor, Augustus himself.

Victory at the races was related to imperial victory, with the emperor being viewed as victorious, regardless of whether he is giving or receiving the crown of victory. The imperial and triumphal character of the obelisk is also reinforced on every side of its base, thus emphasized the order and prosperity brought by imperial rule. Imperial propaganda became especially important following the Goths’ crushing defeat of the Romans at the Battle of Adrianople in 378. The obelisk represented the sun, while the factions represented the four seasons, the chariots represented planets and the seven laps represented seven days of the week. This in turn was related to the imperial order, as all classes of the empire were represented in the spectators of the races, over which the emperor presided.

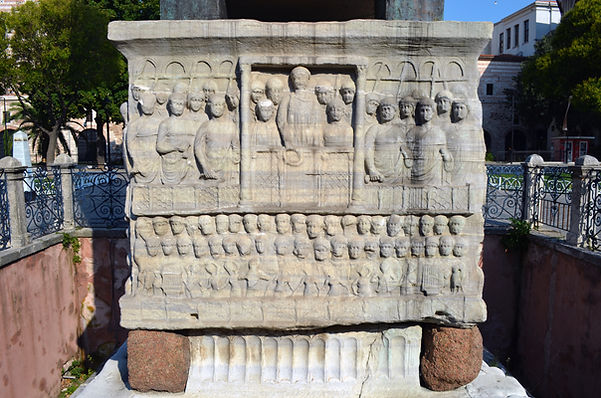

The Obelisk of Theodosius rests on an elaborately decorated base depicting Theodosius and his court at the Hippodrome of Constantinople. Underneath the main Proconnesian marble base (approximately 7 square meters) is another wider base with Greek and Latin inscriptions and hippodrome scenes. In addition, four bronze cubes support the corners of the obelisk, while four granite blocks are set between the corners of the upper base and lower base. The reliefs on the base constitute one of the most important dated pieces of late antique sculpture to survive.

Reliefs on all four sides of the upper base show the emperor and his court attending the games. On each side, the reliefs are divided into two registers by a lattice balustrade that separates the upper tier of seating from the lower. The upper register on each side shows the kathisma – the imperial box at the Hippodrome which was linked with Great Palace. At the center of the upper register is the imperial group, which is flanked by two rows of figures: officials in the front row and Germanic guardsman at the back row. It is possible that these officials were individually portrayed, though it is impossible to confirm due to the current condition of the reliefs. The Germanic guardsmen wear torques around their necks, carry spears, and hold shields. The lower registers differ on each side of the base, with simple tiers of spectators on the southwester and northeastern sides. On the northeastern side, there are two standing attendants standing below the kathisma, next to an arched gateway. This arch gateway is depicted on the southwest side as well.

On the northwestern side, there are four central figures, the largest is Theodosius, while on his left is the Western Emperor Valentinian II (19 years old in 390) and on the left, Arcadius and Honorius (then 13 and 6 years old). Its lower register depicts kneeling barbarians presenting gifts, which was perhaps meant to represent a barbarian embassy. On the southeastern side, the central figure is Theodosius, who stands with the victory wreath in his hand. The two smaller figures beside him are generally identifies as his sons Arcadius and Honorius, the future emperors of the Eastern and Western Roman Empire. On each side, there are several figures depicted in consular dress and holding the mappa – the white cloth dropped to signal the start of chariot race. The southeastern side, below the scene with Theodosius holding the victory wreath, has two tiers of spectators with a third tier of female dancers and musicians playing flutes and water organs.

There are also scenes from the hippodrome on the lower reliefs. On the northeastern side is a depiction of the erection of the obelisk. The northeast face of the obelisk is depicted lying on the ground in front of the Hippodrome’s colonnades. An official (possibly Proclus himself) is directly the workers, who attempt to raise the obelisk with ropes and windlasses. On its southwestern side, the obelisk stands erect on the spina of the Hippodrome, along with the Masonry Obelisk, the metae and perhaps the lap counter. There are four-horse chariots shown racing from left to right below the spina. Above the spina are two figures riding on horseback, presumably victorious charioteers celebrating their victory on their chariot’s lead horse.

In its original setting the obelisk and its base would have only been viewed from a distance in the seating of the Hippodrome and frequently obscured by chariots racing past. While its exact location in the Hippodrome is unknown, it is possible that the obelisk marked the center of the Hippodrome. Furthermore it is possible that the kathisma was directly in front of the obelisk, thus at the center as well. The particular placement of the obelisk base seems to account for the language of the inscriptions: as Latin was the imperial language, it was oriented towards the emperor and his court on the southeastern side, while the circus factions, as representatives of the local Greek-speaking population, faced the Greek inscription on the northwestern side. The orientation of the reliefs on each side perhaps relates to the specific depictions as well.

All four reliefs are symmetrical, abstract, and hieratic, emphasizing Theodosius and the members of his dynasty. The age and seniority of the central figures, for example, are indicated by their size. The emperor's central position of the emperor, along the frontality of the images of the guards, prisoners, and spectators around him, suggests a ceremonial intent for the reliefs. A similar depiction of Theodosius and his court can be seen in the Missorium of Theodosius. The format for imperial representation developed earlier, as seen in the oratio and largitio registers in the Arch of Constantine, and continued later, as seen in the mosaics of Justinian and his entourage in San Vitale in Ravenna. These reliefs, then, can be viewed as a monumental counterpart to the late Roman panegyrics, delivered before the emperor at state occasions.

The imperial and triumphal character of the obelisk is also reinforced on every side of its base, thus emphasized the order and prosperity brought by imperial rule. This was particularly important following the Goths’ defeat of the Romans at the Battle of Adrianople in 378. The relief of Theodosius holding the victory wreath faced the imperial court, implying that all victors are dependent on Theodosius as the giver of victory and of its rewards. The cosmological significance of the obelisk and its circus context also can be seen in these reliefs. Just as the cosmic order is represented in the Hippodrome, so the imperial order is represented on the reliefs, which center of the emperor Theodosius.

Missorium of Theodosius

Southeastern inscription (facing emperor and his court)

Latin Inscription

DIFFICILIS QVONDAM DOMINIS PARERE SERENIS

IVSSVS ET EXTINCTIS PALMAM PORTARE TYRANNIS

OMNIA THEODOSIO CEDVNT SVBOLIQVE PERENNI

TERDENIS SIC VICTVS EGO DOMITVSQVE DIEBVS

IVDICE SVB PROCLO SVPERAS ELATVS AD AVRAS

Difficult once, I was ordered to be obedient to the serene master(s) and, after the tyrant(s) had been extinguished, to carry the palm. All things cede to Theodosius and his un-dying issue. Thus I, defeated and tamed in thirty days, when Proclus was judge was raised to the skies above.

Southeastern side (facing emperor and his court)

Greek Inscription

KIONA TETPAΠΛEYPON AEI XΘONI KEIMENON AXΘOC

MOYNOC ANACTHCAI ΘEYΔOCIOC BACIΛEYC

TOΛMHCAC ΠPOKΛOC EΠEKEKΛETO KAI TOCOC ECTH

KIⲰN HEΛIOIC EN TPIAKONTA ΔYO

Only the emperor Theodosius daring to upraise the four-sided pillar, ever lying a burden on the earth, called Proclus to his aid, and so huge a pillar stood up in thirty-two days.

Northeastern side (facing carceres)

Southwestern side (facing sphendone)

From Julian’s letter to the Alexandrians

“I am informed that there is in your neighbourhood a granite obelisk which, when it stood erect, reached a considerable height, but has been thrown down and lies on the beach as though it were something entirely worthless. For this obelisk Constantius of blessed memory had a freight-boat built, because he intended to convey it to my native place, Constantinople. But since by the will of heaven he has departed from this life to the next on that journey to which we are fated, the city claims the monument from me because it is the place of my birth and more closely connected with me than with the late Emperor. For though he loved the place as a sister I love it as my mother. And I was in fact born there and brought up in the place, and I cannot ignore its claims. Well then, since I love you also, no less than my native city, I grant to you also permission to set up the bronze statue in your city. A statue has lately been made of colossal size. If you set this up you will have, instead of a stone monument, a bronze statue of a man whom you say you love and long for, and a human shape instead of a quadrangular block of granite with Egyptian characters on it. Moreover the news has reached me that there are certain persons who worship there and sleep at its very apex, and that convinces me beyond doubt that on account of these superstitious practices I ought to take it away. For men who see those persons sleeping there and so much filthy rubbish and careless and licentious behaviour in that place, not only do not believe that it is sacred, but by the influence of the superstition of those who dwell there come to have less faith in the gods. Therefore, for this very reason it is the more proper for you to assist in this business and to send it to my native city, which always receives you hospitably when you sail into the Pontus, and to contribute to its external adornment, even as you contribute to its sustenance. It cannot fail to give you pleasure to have something that has belonged to you standing in their city, and as you sail towards that city you will delight in gazing at it.”

16th century engraving by Onofrio Panvinio

Detail from a miniature of Istanbul by Matrakçı Nasuh (c. 1537)

Ottoman acrobats on the obelisks from Hünername (c. 1530)

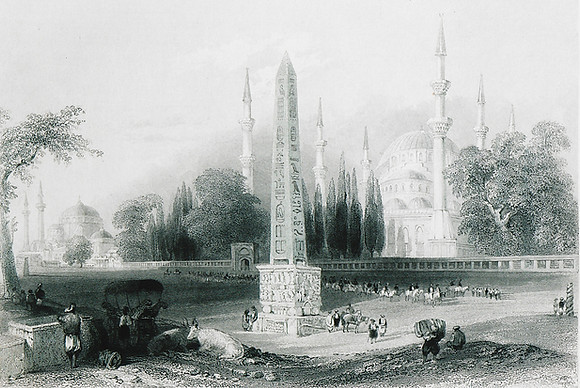

Obelisk of Theodosius and At Meydanı by Thomas Allom (1836)

The Atmeidan, or Hippodrome by W.H. Bartlett (1838)

Obelisk of the Hippodrome by Eugene Flandin (1853)

Photo by James Robertson (1853-1867)

Photo by Sébah & Joaillier (Second half of the 19th century)

Reliefs from the base of the Obelisk of Theodosius by G. Wheler (1729)

Lithograph by Mary A. Walker

Photo by James Robertson (1853-1867)

From the Nicholas V. Artamonoff Collection

Hieroglyphic Inscriptions

Northwestern Inscription

Horus, Strong Bull, beloved of Re, King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Menkheperra, the one who Ra made great, raised Atum as a child in the arms of Neith, the divine mother, as a king, he has conquered all of the earth, with a long life, Lord of the Jubilee…

Northeastern Inscription

High-crowned Horus, beloved of Re, King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Diadems, the one crowned by Maat, beloved by the Two Lands, Menkheperra, the image of Re, Lord of Victory who subdued all lands, established his frontier at the Beginning of the Earth [the extreme south] up to the marshlands of Naharina…

Southeastern Inscription

Horus, Strong Bull, appearing in Thebes, Lord of Two Crowns, enduring kingship like Re in Heaven, Golden Horus, glorious in his radiance, all-powerful in strength, King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Menkheperra, chosen by Re, He made [the obelisk] as a monument to his father, Amun-Re, Lord of the Thrones of The Two Lands, erecting…

Southwestern Inscription

Horus, Strong Bull, appearing with Maat, King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Menkheperra, created by Re, crossing the Great Circle of Naharina [Euphrates] in valour and victory at the head of an army, making great slaughter…

The pyramidion depicts a standing god holding the hand of the pharaoh. On the top of each face of the shaft is a scene of Tuthmosis III making offerings to the god Amun-Re.

Above Amun-Re (Pyramidion): Amun, he gives all life, stability, and happiness, and the kingship of Re.

Above the kneeing pharaoh: King of Upper and Lower Egyptians, Menkheperra, bestows life, stability, and happiness, just like Re in eternity.

Above Amun-Re: Amun-Re, King of the gods, Lord of Heaven, Ruler of Heliopolis, he gives all life, stability, and happiness.

Above the kneeing pharaoh: King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Menkheperra, Son of Re, Tuthmosis, bestows life like Re, forever.

Full southeastern translation (taken from relief at Karnak):

He made as his monument for his father, Amun-Re, Lord of the Thrones of the Two Lands, the erecting [for him of great obelisk of red granite, the pyramidions being of electrum, that he – Tuthmosis III – made be given life Re forever.]

Relief of Tuthmosis III at Karnak with the Theodosian Obelisk and its pair

Photo by kairoinfo4u

Northwestern Side

Northeastern Side

Southwestern Side

Southwestern Side

Northeastern Side

Detail of a map of Constantinople by Braun-Hogenberg (1572)

References

“The Monuments and Decoration of the Hippodrome in Constantinople” by Jonathan Bardill

“Points of View: The Theodosian Obelisk Base in Context” by Linda Safran

“Relief with prize presentation scene from the Theodosian obelisk” by Richard Brilliant

The Urban Image of Late Antique Constantinople by Sarah Bassett

Two Romes: Rome and Constantinople in Late Antiquity edited by Grig & Kelly

Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium by Jonathan Harris

Der Obelisk und Seine Basis auf dem Hippodrom zu Konstantinopel by Gerda Bruns

The Obelisks of Egypt: Skyscrapers of the Past by Labib Habachi

Karnak: Evolution of a Temple by Elizabeth Blyth

The Hippodrome of Constantinople And Its Still Existing Monuments by Grosvenor

Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium edited by Alexander Kazhdan

Sources

The Works of the Emperor Julian, Volume III

Resources

Columns and Monuments of Constantinople Photo Album (Byzantine Legacy Flickr)

Hippodrome (Nicholas V. Artamonoff Collection)

Freshfield Album (Trinity College)

Hippodrome (Byzantium 1200)

Obelisks of 7th Pylon (UCLA Digital Karnak)

Temple of Amun-Re and the Hypostyle Hall, Karnak (Khan Academy)